GALERIE ERIC KLINKHOFF

Lilias Torrance Newton, R.C.A. (1896-1980)

We buy and sell paintings by Lilias Torrance Newton. For inquiries, please contact us.

In many ways the story of Lilias Torrance Newton – portrait painter, art teacher, abandoned wife, and mother – reads like a story of the 1990s. But what seems banal today was exceptionally sixty years ago when divorce was frowned upon and married women were not expected to work outside the home. Few of the women that Lilias Torrance Newton met in art school tried to combine marriage with a professional career. Regina Seiden, a fellow student, gave up painting soon after marrying painter Eric Goldberg in order to devote herself to her husband’s career. Of the ten women who are know today as the Beaver Hall Group, Lilias Torrance Newton was the only one who married.

Lilias Torrance was born in Lachine, Quebec, on 3 November 1896, the fourth child and only daughter of Alice Mary Stewart Torrance, Lilia’s father, Forbes Torrance, a businessman and member of Montreal’s Pen and Pencil Club, died a month before her birth. Lilias and her family soon mover to Berthier, Alice Torrance’s hometown, and then to Kingston, where Lilias went to public school. After breaking her leg in a tobogganing accident, Lilias whiled away here long convalescence by drawing and studying her father’s sketchbooks. In 1908, the family returned to Lachine. Lilias attended a local school run by the Reverend Hewton (father of painter Randolph Hewton) and took drawing classes at the Art Association of Montreal (AAM).

In 1910, she entered Miss Edgar’s and Miss Cramp’s School as a boarder. Her three years at this prestigious girls’ school gave her the poise and self-confidence to mingle easily with the professional men and society ladies who later became her clients. At sixteen, she left school to study full time with William Brymner at the Art Association of Montreal, winning a scholarship in the Life class in her first year.

William Brymner, Director of the AAM school from 1886 to 1921, was in inspiring teacher, who imbued his students with a belief in the importance of art. Many of the students were middle-class girls whose parents considered painting a desirable accomplishment for their daughters, rather than a means of earning a living. Brymner encouraged his female students to adopt a professional attitude toward their work and to complete their training in Paris. According to Lilias’s friend Anne Savage, “[Brymner] possessed that rare gift in a teacher never to impose his own way on his pupils. ‘Work out your own salvation in fear and trembling’ he would admonish us and leave us to struggle on.”

A year after Lilias began her studies with Brymner, the First World War broke out. Most of the young men who she knew, including her three brothers, her friends’ brothers and fellow students (like Robert Pilot), joined up. In 1916, after hearing that one of her brothers had been killed in action, Lilias sailed for England with her mother, in order to be near another brother who was training there. (He, too, was subsequently killed.) While in London, Lilias worked as a volunteer for the Canadian Red Cross, arranging billets for wounded Canadian officers. Through this work, she met her future husband, Lieutenant Frederick Newton (1896-1976), who had been seconded from active service to help with the billeting. She also managed to continue her art training, taking classes twice a week from Alfred Wolmark, an English painter. After the war ended, she stayed on in London for six months to study with Wolmark full time.

Lieutenant Frederick Newton (1896-1976), who had been seconded from active service to help with the billeting. She also managed to continue her art training, taking classes twice a week from Alfred Wolmark, an English painter. After the war ended, she stayed on in London for six months to study with Wolmark full time.

On her return to Montreal in 1919, Lilias Torrance set out to establish herself as a professional painter. In order to do so she needed a studio, models, and an outlet for her work. At that time there were only a few private galleries in Montreal, most of which specialized in European art. Painters were dependent on the big annual exhibitions of the AAM and the Royal Canadian Academy (RCA). A.Y. Jackson and Randolph Hewton, who had recently returned from the war, believed that the more progressive artists should band together to get their work shown and to overcome the critics’ resistance to modern art. In early 1920, Jackson and his Toronto friends formed the Group of Seven. A few months later the Montreal painters began to organize. Lilias Torrance, Mabel May, Randolph Hewton and Edwin Holgate formed the nucleus of the Montreal group. Since they were using a house on Beaver Hall Hill as studio space and planned to hold exhibitions there, they called themselves the Beaver Hall Group.

Lilias Torrance Newton, R.C.A. (1896-1980)

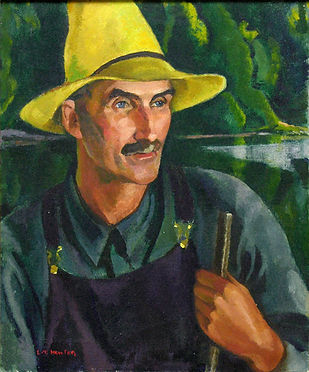

"The Guide Millette"

Oil on canvas 24 x 20 in. (SOLD)

Lilias Torrance Newton (1896-1980)

"Portrait"

Oil on canvas 36 x 28 in. (SOLD)

From the beginning, women played an important role in the Beaver Hall Group. In January 1921, when the Group held its first “annual show,” it numbered eight women among its nineteen members. The male artists, with the exception of Randolph Hewton, lost interest in the Group, but the women used the studios regularly and invited friends to take up the vacant space. Lilias Torrance and Mabel May occupied the largest studio, where they taught a women’s class on Saturday mornings. Anne Savage shared a studio with Nora Collyer. Prudence Heward and Sarah Robertson, who were still at the AAM school dropped in to see their friends work. According to Anne Savage it was a time of great excitement. Although the women had to give up the house eventually, the camaraderie they had established continued for years. They phoned each other regularly to exchange news of the art world and met at teatime to discuss their work.

On June 1, 1921, Lilias Torrnace married Frederick Newton at St. Paul’s Church in Lachine. She was 24 years old and had already sold a portrait, Nonnie (1921), to the National Gallery of Canada. According to Montreal Painter Marian Scott, Lilias Torrnace only agreed to marry on condition that she could spend six months of the year studying in Paris. Whether or not this story is literally true, it suggests Lilias Torrnace Newton’s commitment to painting. In the event, she visited Paris twice. In 1923, she spent four months studying with Alexandre Jacovleff, a Russian artist who was considered the finest draughtsman in Europe. In his Life class she stopped painting and worked on large chalk drawings to give her figures greater solidity. The improvement can be seen in Anna (1923), the first canvas she painted after her return to Montreal. Lilias Torrance Newton did not get back to Paris until 1929 – and this time she was accompanied by her three-year-old son Francis Forbes and his nanny. Little is known about this trip, but Newton probably spent much of her time touring the galleries, as she had on her earlier visit. The painters that interested her particularly were the Italian figure-painter Modigliani and the Fauve painters Valminck and Derain. Lilias Torrance Newton’s Self-Portrait (c. 1929) depicts her as a self-confident young professional. The figure, cropped just below the bust, dominates the space and the expression is one of deep concentration. The freely-brushed background is broken only by the bottom of a picture frame (or window) and the silhouette of the palette. By representing herself as a painter Lilias Newton places herself within a tradition of self-portraiture that goes back to the Renaissance, while simultaneously challenging the traditional concept of the artist as male.

In 1927 a long article on Lilias Torrance Newton appeared in Saturday Night, praising her psychological insight and singling out the portraits of Dr. C.S. Fosbery, founder and headmaster of Lower Canada College, and Mrs. John Savage, the mother of Newton’s friend Annie. As the writer suggests, the portrait of Helen Galt Savage (1857-1942), a descendant of the novelist John Galt and a retired teacher, conveys “the intrepid spirit and fine pride” of the sitter. The article goes on to portray the 31-year-old Newton as a kind of “superwoman.” Already an associate member of the Royal Canadian Academy, Newton had sold three paintings to the National Gallery of Canada and exhibited abroad at the Paris Salon (1923), at Wembley, England (1924 and 1925), and at the Panama Pacific Exhibition in Los Angeles (1925). These achievements, along with motherhood and marriage to a “most helpful and sympathetic husband,” make it appear that Newton is living a charmed life. The article fails to mention that in order to lead such a life she needed a studio, domestic help, and firm financial backing. All of these things, which she could take for granted in 1927, were jeopardized where her husband, a stockbroker, suffered heavy losses in the Wall Street crash of 1929.

Lilias and Fred Newton may have been temperamentally unsuited, as Fred’s brother Ted suggested. In any case, the couple’s relationship deteriorated after the stock market crash when Fred Newton began to drink heavily. In May 1931 he left Montreal and never say his family again. Two years later, Lilias Newton obtained a divorce by parliamentary decree on the grounds of her husband’s adultery.

Faced with the problem of supporting herself and her son, Lilias Newton looked for ways to make her painting pay. The Depression had already affected artists’ sales. Private galleries were struggling, and some like William Scott’s of Montreal finally closed. The National Gallery, which had actively supported Newton and other modern painters, suffered a budget cut from a high of $130,000 in 1929 to $25,000 in 1934. Eric Brown, Director of the National Gallery, did what he could to help Lilias Newton. In 1932, he commissioned a posthumous portrait of Dr. Francis Shepherd, former chairman of the Gallery’s trustees, and in 1933 he sat for his own portrait. Alice and Vincent Massey, discerning private collectors, also helped Newton, commissioning four family portraits from her.

In 1933, to combat the effects of the Depression, the surviving members of the Group of Seven invited some of the Beaver Hall painters and a few others to form the Canadian Group of Painters (CGP). Lilias Torrance Newton was one of the original 28 members. In November 1933, she submitted four works, including Nude in a Studio (1933), to the Canadian Group exhibition in Toronto. Much to her disappointment, the Art Gallery of Toronto refused to hang Nude in a Studio, on the grounds that the model’s open-toed shoes rendered her offensively naked. Newton’s misfortune came to the attention of the Masseys, who bought the painting, motivated partly, according to A.Y. Jackson, by “the idea that she was not getting a fair deal.” The next year, when the Masseys exhibited their collection at the Art Gallery of Toronto, the nude was hung, along with Newton’s portraits of Vincent and Alice Massey. These full-length portraits, which were also shown at the 1935 RCA exhibition in Montreal, established Newton’s reputation as a portrait painter.

In her first years as a single parent, however, Lilias Newton had to supplement her portrait commissions by teaching. Discussing the Depression with Charles Hill in 1973, Newton said: “I don’t suppose any of us would have made a living if it hadn’t been for teaching.” She started with a few pupils in her studio and in 1943 joined up with Edwin Holgate to teach the Life class under the auspices of the Art Association of Montreal. After two years, the artists resigned as they found that they were not getting a sufficient return for their work. In 1936, they were persuaded to come back under a different arrangement. Teaching did not come easily to someone of Newton’s temperament. She was too impatient. Jeanne Rhéaume, who took her Life class, told me that Newton would sometimes paint on her students’ work, thus robbing them of their incentive. In May, 1940, Newton and Holgate resigned, this time for good. Newton, who underwent a hysterectomy that summer, was probably exhausted from trying to pursue a double career.

During these busy years, Lilias Newton had little time to spend with her son Forbes. She managed with daily help at first and later sent Forbes to board at Upper Canada College in Toronto. During the summer holidays she rented a cottage at St. Adolphe de Howard in the Laurentians. This was a time of fun and relaxation for them. Both. As a change from her regular work, Newton painted still lifes or persuaded one of the villagers to pose for her. Two of her most intimate portraits, Maurice (1939) and My Son (1941), were painted in the cottage at St. Adolphe. In the painting of Maurice Alaric, a local boy, Newton captures the restlessness and self-absorption of youth. The steps in the background serve both a formal function – echoing the line of the head and shoulders – and s symbolic purpose, suggesting the unfinished quality of adolescence. The staircase motif may have been suggested by Prudence Heward’s portrait of a young French-Canadian boy, Rosaire (1935), which was shown at the AAM Spring Exhibition in 1939.

Among Lilias Newton’s most successful works are her portraits of fellow artists: A.Y. Jackson (1936), Edwin Holgate (c. 1937), Louis Muhlstock (1937) and Frances Loring (c. 1942). In the portrait of Jackson, the broad shoulders, “bulldog” chin, and direct gaze suggest the sitter’s energy and determination. The background of snow-covered hills, which Jackson drew in himself, reinforces his image as a virile outdoor painter.

Painting a woman was a rare treat for Newton, since most of her commissioned subjects were male. “There is more colour to work with, and I feel I can paint a more imaginative portrait of a woman,” Newton explained, “because of her clothes, through which she expresses herself. Newton seized the opportunity to play with colour in her portrait of sculptor Frances Loring wearing a bright red shawl draped over a low-cut yellow bodice. There is a monumental quality in the handling of the drapery and the modeling of the head, while the expression suggests the inner strength and vision of this unconventional woman.

Lilias Newton was elected to full membership in the Royal Canadian Academy in 1937, only the third woman to be so honoured by that patriarchal association. The portrait of Louis Muhlstock, which she presented as her diploma piece, is a “masterful composition of triangles,” as art curator Dorothy Farr remarked. The arched eyebrows, bent elbows and splayed finders echo the triangular shape of the face. Muhlstock’s unusual pose – seated backward on a chair with hands gripping the frame - and the downward thrust of his eyes suggest impetuosity and intensity.

Lilias Newton continued to contribute to CGP exhibitions and to international shows like the Southern Dominions Exhibition (1936) and the Coronation Exhibition in London (1937). Although these shows generated few sales, they kept her name before the public. In 1939, she had a one-woman show at the AAM and in 1940, exhibited with A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer and Edwin Holgate at the Art Gallery of Toronto. Reviewing the former exhibition for the Montreal Gazette, a critic remarked on the “refreshing enthusiasm” in Newton’s work. “Here is no set formula . . . but the impression conveyed is that each sitter presented a fresh problem which challenged the brush of this gifted Montreal painter.”

In 1941, artists and art lovers from across Canada assembled for a special event, the Kingston Conference at Queen’s University. According to Lilias Newton, one of the 154 participants, the artists had a wonderful time getting to know each other. One of the main themes of the Conference, which took place only a few days after Hitler invaded Russia, was the role of the artist in wartime. Toronto sculptor Frances Loring urged that a campaign be undertaken to persuade the public that “the artist really has something to say which will be a contribution towards the success of our war effort and towards the life of our community.

In the autumn of 1942, a war records project was set up under the direction of Vincent Massey, Canadian High Commissioner to England, and H.O. McCurry, Director of the National Gallery. By 1945, 33 artists had been commissioned, including Lieutenant Molly Lamb [Bobak], the only woman war artist to hold a military rank. Vincent Massey tried to get an official commission for Lilias Newton. “[She] would I am sure do an extremely useful job here and her sex ought to be no bar,” he wrote to McCurry (6 October 1943). “There was the same attitude expressed to the organization of the women’s services early in the war but it seems archaic now.” Despite Massey’s follow-up telegram to the Secretary of State in July 1944, Newton was not appointed. Thanks to McCurry, however, she received a commission in 1942 to paint two portraits which were reproduced on recruiting posters and postcards: Canadian Soldier No. 1 and Wing Commander W.R. MacBrien, RCAF.

The war years may have been difficult for Newton emotionally, awakening memories of her dead brothers and raising fears for her son, who enlisted in the Canadian Air Force. Professionally, however, she flourished. In 1943, she painted a fine portrait of her old friend Professor Gillson in his uniform as wing commander in the Canadian Air Force. She spent part of 1944 and 1945 in Toronto, painting portraits for boardrooms and head offices. This type of work paid well. Her portrait of R.Y. Eaton, President of the Art Gallery of Toronto (1944) fetched $1000. Although Newton sometimes got tired of the “commercial end of it,” as Jackson suggested, she enjoyed the fellowship of the Studio Building, where she rented a studio from Lawren Harris Jr. A photograph in Saturday Night, 10 March 1945, shows Newton drinking coffee with fellow artists Jackson, Frances Loring, and Florence Wyle in “the Shack” that had once belonged to Tom Thomson.

After the war, Newton criss-crossed the country painting influential men (and occasionally women) in Ottawa, Toronto, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver. Her subjects ranged from the Governor General, Earl Alexander of Tunis, to golfer Sandy Somerville and skier Margaret Morrison. Her new affluence enabled her to visit Mexico in the late 1940s and Italy in 1953. She gave up her studio apartment on Pine Avenue in 1956 for a penthouse on the corner of Sherbrooke and Guy. From her new 30-foot studio, which had once been a billiard room, she enjoyed a spectacular view of Mount Royal.

Lilias Newton’s commission to paint the Queen and Prince Philip for Rideau Hall aroused great public interest, since it was the first time a Canadian had been entrusted with such a commission. Interviewed by a Gazette reporter before her departure for London, Lilias Newton explained that she liked to begin with a few quick sketches. “It’s impossible to jump into a portrait, it takes time to make up my mind about the best, the most attractive pose, and as I sketch, my subject becomes more natural, more unconscious, and I catch an impression that I may have missed at first.” In her diary for March 14, 1957, Newton notes, “First sitting [with] Queen. Pretty, shy, stiff in pose. Considerate, but not easy.” The portraits were not a complete success, probably because Newton was unable to establish an easy rapport with her sitters. She was sufficiently pleased with a preliminary sketch of Prince Philip, however, to hang it in her studio in The Linton.

In 1961, Lilias Newton helped raise money for the Victoria Order of Nurses, by offering to paint the portrait of the winner of the VON raffle. Freda Armstrong of Westmount, an amateur painter, won the raffle, which raised $5000, enough to replace one VON car.

Newton had a genuine interest in people. She told critic Robert Ayre that when she was not painting them she was observing them, “in the street, on the bus, in the shops.” Her success as a portrait painter was due as much to her rapport with her subjects as to her technical brilliance. She liked to talk to her sitters while she was painting. The liveliness of her best portraits comes from the excitement she felt in getting to know her sitters, many of whom became friends. But the disadvantage was that she was always obliged to move on—to other portraits and other friends. Underneath the charm that made Newton such a popular dinner guest, there was a shell of reserve. She had few real intimates. Her mother died in 1925 and her third brother Stewart Torrance in 1942. Her ties to the Beaver Hall women grew weaker as she spent less time in Montreal. Her son, a consulting engineer, moved frequently and eventually settled in the United States. As Newton grew older, she struggled with periods of depression and increasing deafness. But she retained her sense of humour and her interest in young people. Two McGill students, Eric Klinkhoff and Allan Case, who modeled for her when her clients were too busy to sit, enjoyed their sessions in the studio and sometimes took Newton (then in the late seventies) to lunch or a movie. Despite her wit and sparkle in public, I suspect that Newton was a lonely woman.

She continued to paint until 1975, when she fell and broke her collarbone. She died in a nursing home in Cowansville, Quebec, 10 January 1980, at the age of 83.

Art Historian Dennis Reid has claimed that “by the mid-forties [Newton] had painted most of the famous Canadians of the time.” She brought a welcome informality to Canadian portraiture, encouraging her subjects to adopt unconventional poses. In Lady in Black (c. 1936), Mrs. Gillson, wearing a formal evening dress, sits with her feet tucked under her body. Not all of her subjects were famous. Some of her most charming paintings are of children (Portrait of Winkie, 1929, which depicts here three-year-old son), young girls (Martha, 1937), and ordinary people (Frère Adélard, 1939, painted at St. Adolphe). The need to support her son led her to take a certain career path. Had she been free to choose her own subjects, we might have had more strong portraits of women like Mrs. John Savage and fewer men in academic or legal robes.

“The impact of the sitter’s personality on mine is what I paint,” Newton said, adding that there must be sympathy between the sitter and the artist for the portrait to be good. By her own count she painted about 300 portraits, ranging from statesmen and bishops to financiers, artists, sportsmen and sportswomen. In the best of them she manages to evoke the individuality of the subject and to suggest something of her own passionate interest in people.

Source: Lilias Torrance Newton Retrospective Exhibition Catalogue, Galerie Walter Klinkhoff, 1995.

Text written by Barbara Meadowcroft.

© Copyright Barbara Meadowcroft and Galerie Walter Klinkhoff.